Geiger Counter Improvements

2024

The first version of my Geiger counter board has one obvious limitation: it is USB powered and can't be used without an external power source. I added an internal 18650 cell lithium ion battery in the second revision. This worked fine, but I wanted to add support for Geiger tubes beyond SBM-20 and also wanted to upgrade to a through hole USB-C connector after ripping the surface mount micro-USB connectors off of the board by accident more than once. In addition to supporting more Geiger tube sizes and adding a more rugged USB connector, I also updated the design for automated assembly by JLCPCB so that I can have a few spares without spending all day soldering.

I was finally inspired to complete this project after coming across radiological contamination area under the McKinley bridge in St. Louis Missouri next to Mallinckrodt. I didn't have to go out of my way to find this; it was literally in the middle of the bike trail which has now been routed around it. Significant quantities of Uranium ore were processed in St. Louis at Mallinckrodt Chemical Works in support of the Manhattan Project, and the site I came across is between that facility and the Mississippi river.

Open Air Radiological Contamination Pit Near St. Louis Mallinckrodt Facility

Version 2 Improvements

- Added an 18650 battery holder.

- Added a power switch.

- Added a battery charge IC and undervoltage protection.

- Added overvoltage protection circuit to Geiger high voltage supply.

I've designed a several lithium-ion powered boards before that use buck-boost converters to power their 3.3V microcontrollers, but here I was lazy and powered the 3.3V ESP32 with a low dropout linear regulator connected to the battery. I set an undervoltage protection limit of 3.2V (the ESP32 will get squirrely as you undervolt it) which results in something like 70% of the capacity of the lithium-ion battery being useable. My laziness was driven by the integrated buck-boost part that I had used in the past being out of stock and subsequently not feeling like finding a new part and adding it to my library.

Finished Geiger Counter

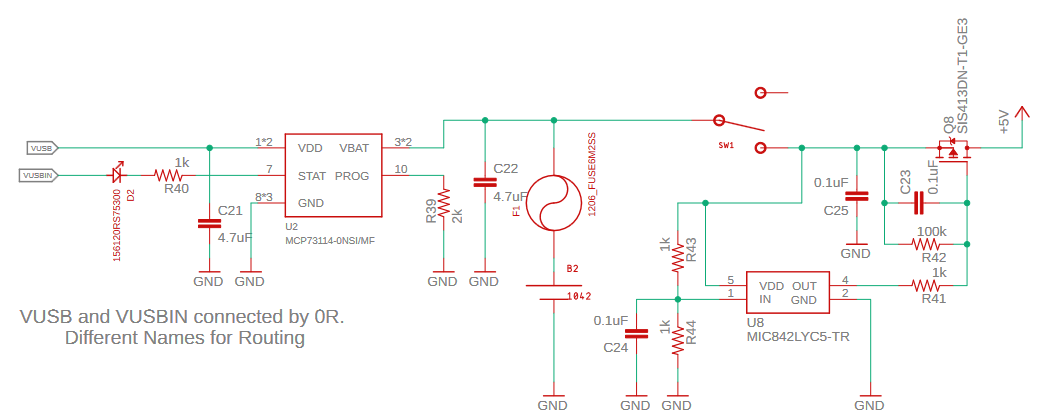

Battery Charge and Protection

Lithium ion battery require some additional protection for reliable and safe operation. You need to ensure that the voltage, current, and temperature limits of the battery are not exceeded. For current limits, I added a PCB fuse since the only situation where discharge current 100mA would be expected is short circuit, and the linear battery charger IC I selected sets the charge current limit. I ignored temperature limits which is not uncommon for low power products with slow charging circuits like this. Even if the board is left in the sun while charging, nothing should get hot enough to actually be dangerous. For voltage protection, the linear battery charge IC sets the maximum voltage and a comparator based under voltage protection circuit protects against overdischarge.

Battery Charge and Protection Circuits

The previous board had no use for a power switch since it was USB powered, so I had to add one here. I used a right angle switch from the 100 series of E-Switch. These are pricy (like most electromechanical hardware) but are great quality and are available in many different configurations (mounting options, poles, momentary).

Battery Charge IC

MCP73114-0NSI/MF is a battery charger IC well suited for charging lithium ion batteries off of a 5V source. It provides a charging indicator light and has a resistor programmable charge current limit. In this case, I set the charge current to 500mA so that the IC didn't get too warm and so that I wouldn't have trouble charging off of typical USB ports. While the USB spec specifies that standard USB 2.0 peripherals can only draw 100mA without further negotiation, no OEM worth their salt will design a USB port not capable of supporting 500mA these days due to the proliferation of non-compliant USB accessories. The '-0NS/MF' at the end of the part number sets the charge voltage to 4.2V.

Undervoltage Protection Comparator

An open drain comparator with an internal reference (MIC842LYC5-TR) controls a P-channel MOSFET acting as a high side switch to enforce an undervoltage limit on the battery. The internal reference is nice here because it both eliminates an external reference part and also ensures low quiescent current: cheap shunt voltage references require significant bias current and low quiescent current series voltage references are more expensive. I set the undervoltage limit to about 3.2V (the schematic does not reflect what I ultimately came up with on the bench).

Boost Converter Overvoltage Protection

The output voltage of the high voltage supply for the Geiger tube is nominally set by the peak current of the inductor triggering reset of the 555 timer by the voltage across a current sense shunt exceeding the base to emitter threshold of an NPN BJT. As simulations for the last board showed, this results in a highly temperature dependent output voltage. This alone is OK, but because the output voltage needs to be adjusted with a potentiometer, the potential exists to set the output voltage too high (in excess of the rating sof the diode and BJT). In practice, it seems that non-destructive breakdown mechanisms in these parts limit the output voltage, but this is achieved by operating the parts past their absolute maximum ratings which is never good to bank on. To add some protection against this, I added a second reset NPN with its base connected to a voltage divider from the output. The voltage divider adds a load to the output, but this actually stabilizes the output voltage somewhat since with no-load the output voltage is defined by the switching losses and diode leakage (which will be temperature dependent) only. I set this limit to 500V to provide plenty of headroom above the nominal 400V output.

Version 3 Improvements

- Added buck-boost regulator.

- Changed USB connector to USB-C.

- Changed battery charge IC to a cheaper option.

- Changed the battery protection circuit to a cheaper option.

- Optimized for parts supported by JLCPCB assembly.

- Added support for different length Geiger tubes.

I had to buy a particularly low drop out LDO for the previous version to have anywhere near acceptable battery life — I initially bought a woefully inappropriate one and had to perform initial bringup by charging the battery to 3.3V and shorting actoss the regulator. Given that there isn't a huge cost delta between high performance LDOs and buck boost converters, I bit the bullet and designed in a propper buck boost converter in stock at JLCPCB: TPS63000. This part has an input range of 1.8-5.5V which is perfect for a single cell lithium ion battery, but (very annoyingly) it does not have a precision enable threshold, so it is necessary to keep an undervoltage protection circuit on the battery.

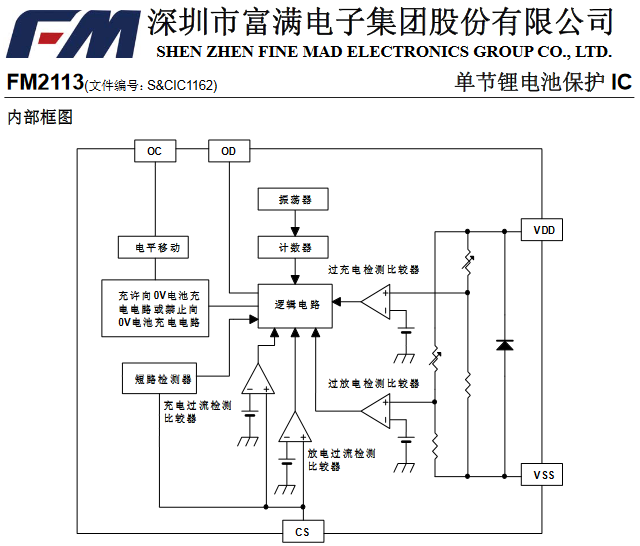

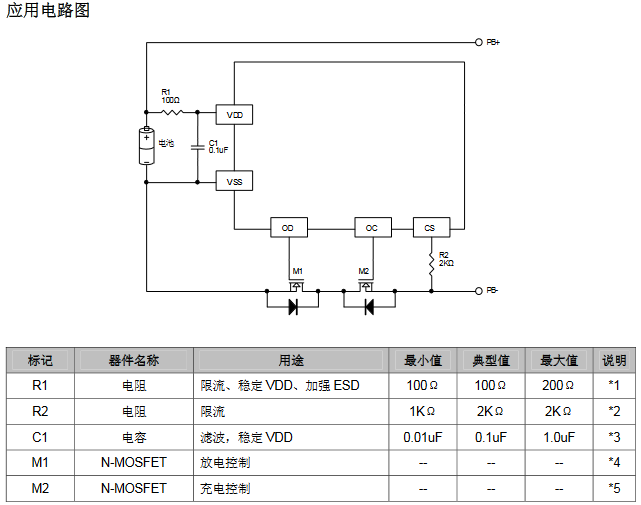

Battery Protection

The undervoltage protection comparator on the previous design worked OK but required manual tuning with who-knows-how-good performance unit-to-unit, so I added a propper battery protection IC. Since I am using JLCPCB as my assembler, I went with the cheapest protection IC that they have high stock of. This ended up being FM2113 which has a datasheet in Mandirin:

FM2113 Block Diagram

Its kind of fun (type-2 fun — quite frustrating in the moment) to find and implement these kind of parts from JLCPCB. It is actually more challenging to find appropriate parts given JLCPCB's attrocious search interface than it is to implement from a foreign language datasheet. I threw a couple key phrases into Google translate to confirm my assumptions, but for the most part I could make out what I needed to do from the block diagrams:

FM2113 Typical Application

USB-C

The previous version of this board used a surface mount micro USB connector, and I managed to rip one off of a board which required careful rework and epoxy to fix. Through hole USB-C connectors are much stronger and are the future, so I switched to that for this version. For an overview of how to upgrade a micro-USB design to USB-C, take a look at this Hackaday article. LINK

There are two sideband use pins on USB-C connectors which are often used these days to break out a second USB 2.0 pair for debug use. I hooked up the UART TX line (with BOM selectability of another GPIO pin) of the ESP32 to the SBU1 pin in case I ever wanted to interface this board with another of my project boards that doesn't support USB. One possible use case I was thinking about was having the ESP32 output discrete pulses for each radiation event over this sideband interface so that another board with a GPS could associate activity with location.

Surface mount micro USB connectors are pretty fragile. I have seen a fair number of >$1000 development boards destroyed after someone snags the USB cable while walking by and rips the connector off od the board traces and all. I had that happen with one of the V2 Geiger counters (and my Nano VNA...) but in both cases I was lucky that there was still enough of the pad on the board that I was able to rework new connectors back on. I secured the new connector with some epoxy, but for V3 I decided to upgrade to a nice sturdy through hole USB-C connector. Since phone chargers have all moved over to USB-C, I think it makes sense to use USB-C on most all newly designed portable products.

One goal of this version of the Geiger counter was to have as many parts installed by JLCPCB as possible I ended up only needing to install:

- The through hole USB-C connector.

- The through hole piezo buzzer and header.

- The power switch.

- The fuse holders.

- The reverse mount LEDs.

- The voltage adjustment potentiometer.

To achieve this goal, I had to change the battery charge and protection circuitry to something that was in stock on JLCPCB.

Software

All three versions of this board enumerate as USB virtual serial ports, but now that this board can operate without a USB cable connected, I added support in software for bluetooth. It's crappy copy pasta of examples, and it doesn't work with iPhones (they have neutered support for classic Bluetooth if you don't pay them) but it works reasonably well for Android. This lets you see real numbers on your phone instead of just listening to clicks.

The name of the Geiger counter bluetooth device is "Geiger-12345" where 12345 is a somewhat unique sequence of five numbers taken from the base mac address of the esp32 chip. I use an Android app called "Serial Bluetooth Terminal" to interface with the Geiger counter.

The Arduino sketch can be on the Github project.

Utility of High Rate Tubes

Probably the most important special equipment that would be needed—and the least improvisable—would be radiation meters of various kinds. These are not only useful during and immediately after the attack; they are necessary for many basic and important postwar activities. Meters could play an essential role in maintaining the morale and the risk-taking capacity of the cadres who would be exposed to radiation. It is easy to see why this is so. The radiation from fallout has curious and frightening effects. Most people already know, or will know in a postattack world, that if you get a fatal dose of radiation the sequence of events is about like this: first you become nauseated, then sick; you seem to recover; then in two or three weeks you really get sick and die. Now just imagine yourself in the postwar situation. Everybody will have been subjected to extremes of anxiety, unfamiliar environment, strange foods, minimum toilet facilities, inadequate shelters, and the like. Under these conditions some high percentage of the population is going to become nauseated, and nausea is very catching. If one man vomits, everybody vomits. It would not be surprising if almost everybody vomits. Almost everyone is likely to think he has received too much radiation. Morale may be so affected that many survivors may refuse to participate in constructive activities, but would content themselves with sitting down and waiting to die—some may even become violent and destructive. However, the situation would be quite different if radiation meters were distributed. Assume now that a man gets sick from a cause other than radiation. Not believing this, his morale begins to drop. You look at his meter and say, "You have received only ten roentgens, why are you vomiting? Pull yourself together and get to work." This view is in accord with experience in peacetime disasters that have been complicated by epidemics. People often require some kind of talisman before they will expose themselves—a shot, a pill, a gauze bandage around the nostrils and mouth or, in this case, a meter. They need, of course, other equipment in addition to meters, but a meter may well be the most essential. In the RAND civil defense study we suggested the immediate purchase of about $100,-000,000 worth of radiation meters, so that this nonimprovisable but vitally necessary piece of equipment will be available.

Background Radiation on a Commercial Flight

As a result, radiation on a commercial flight will typically be 10-100x higher than radiation on the ground. The plot here was recorded by one of my Geiger Counters on a flight between St. Louis, MO and Seattle, WA.